In the early morning hours of September 1, 1918 the east bound Boston freight passed through Vernon at about 2:30 a.m., and was struggling to make its way up the long grade to Bolton Notch with its thirty-seven cars, plus two cabooses, in tow. Unable to get over the final grade near Bolton Notch, the crew employed a practice known as "doubling the hill". They stopped the train, uncoupled the last seventeen freight cars, and left them standing on the track near the club house. They continued on with the first twenty cars towards the crest of the hill, with the intent of setting those cars on a passing siding at Steel’s Crossing. Then the locomotive would return to the freight cars and two cabooses left standing at the club house, pull them to Steel’s Crossing, reassemble the train and continue on to Boston.

But before reaching the crest of the hill with the first half of the train, the two rear cars, steel hoppers loaded with coal, uncoupled, and began rolling back towards Vernon. The telegraph operator at Steel’s Crossing was unaware of the situation, so he could not warn the operator at the club house that two cars were loose, and headed towards the seventeen left standing at his location. The two runaway cars, gaining speed all the time, crashed into the cars at the club house, setting them in motion. The brakes on those cars were not set tight, and all seventeen of them, along with the two cabooses, began rolling downhill towards Vernon. The two loaded coal cars that had broken loose initially derailed in the collision.

As the runaway cars rounded the curve, the flagman, whom had been stationed down the tracks to protect the rear of the stopped portion of the train, realized that there was a problem, and knowing that an employee was sleeping in the rear caboose, he jumped on to warn him, no doubt saving his life. The employee, Ignatius McDowell, an 18-year-old brakeman, was “deadheading” back to his home in Boston. After awakening and informing McDowell of the serious situation, the flagman jumped from the train. McDowell, realizing that it is all down hill to Hartford, sprang into action, and managed to get hand-brakes set on five of the cars as the runaway train continued to pick up speed. Realizing that he was almost to Vernon station, and that a collision with the east bound Providence freight waiting there was imminent, he jumped off of the train just east of the station, tumbling down the steep embankment, but escaped injury.

The operator at the club house, also aware of the Providence freight waiting on the east bound track at Vernon for a clear signal to proceed, telegraphed a warning to Vernon. The engineers of the two locomotives on the Providence freight heard the warning, and had just left their locomotives when the red, end of train marker light, appeared coming around the curve at high speed on a collision course with their train. Conductor Webster, realizing that the runaway cars would need to be derailed to avoid a much worse disaster, threw the switch onto a derailing track.

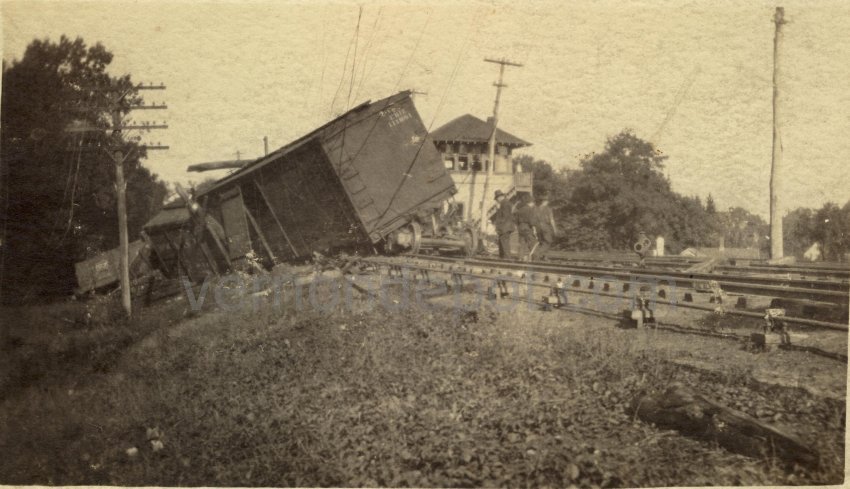

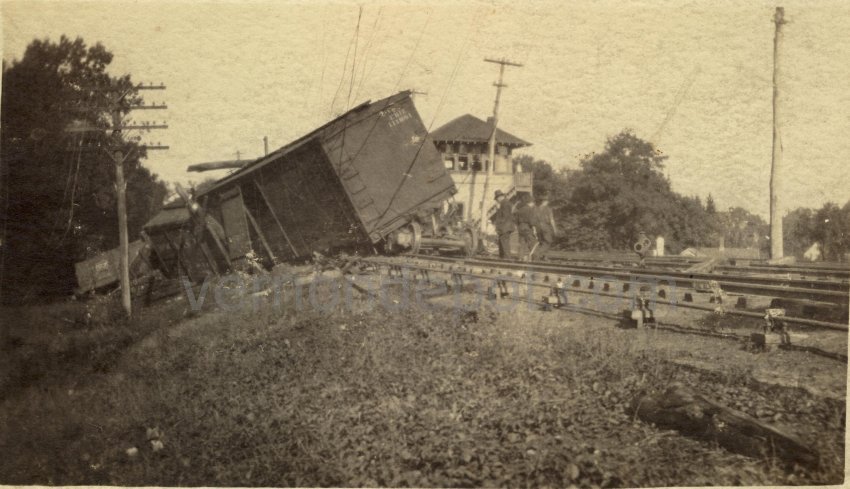

The derailing track, just south of the Vernon interlocking tower, lead into a deep gully on the south side of the tracks, into which the cars were turned. McDowell’s caboose was first in, careening to the bottom of the ditch, and standing on its end. The second caboose passed clear over the first, only to be crushed by the next two cars loaded with cement. The next car was a refrigerated car, scattering its load of fruit as it smashed into pieces. Most of the other cars that followed were loaded with coal and they two were all piled up in the mess.

The wreck took down poles carrying Western Union wires, signal wires between Vernon and Burnside, power wires for the interurban, and telephone lines. The east bound tracks were blocked until two wrecking crews, one from Hartford, and the other from New Haven, cleared a passage about 3 o’clock in the afternoon. The only person to be injured was a man named George Wheeler of Willimantic. He had been working at a tobacco farm in East Windsor Hill and had failed to reach Hartford in time to catch a train home. He instead, took an interurban to Vernon, knowing that he could catch an east bound freight home. He had been riding one of the coal cars and was unable to jump off. When the cars went over the embankment, the shifting load trapped his leg. His injury is said to have been a splintered bone in his leg. We waited at the Vernon Station until the 9:30 a.m. train to Willimantic came through and took him home.